海賊と呼ばれた男(Kaizoku to Yobareta Otoko), tells the story of a Japanese self-made man, Kunioka Tetsuzô, who was called “the pirate”. Along with the history of Japan in the 20th century, here comes this entrepreneur of the crude oil, from his beginnings as a modest local distributor to his days as an oil magnate after World War II. Short-tempered and workaholic, he also shows a nicer side: his devotion to his workers. But that doesn’t come for free: he requires from them a likewise allegiance to the company and its leader: himself. A metaphor for the well-known —now in his last days—relationship between Japanese big companies (大企業, Dai Kigyou) and their employees, Tetsuzô, or 店主(Tenshu ,small-shop boss), as he likes to be addressed by his acolytes, sometimes puts their health and lives at risk through insalubrious tasks or through really dangerous endeavors, as when he sends a tanker with a considerable crew to England-blocked Iran, and his ill-dutiful captain doesn’t mind to charge towards a British warship.

Nowadays, we still see how many Japanese companies (public and private) force their employees to work overtime (残業, Zangyou) beyond the law in a tradition that made possible the Japanese economic miracle of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. Being the legal cap 45 hours of monthly overwork, special provisions signed by half of the employees elevates that figure to 80. And there have been cases of going further than 100 hours of monthly overwork, most times unpaid. Of course, consequences for health are extremely serious, and the high number of excess of work-related deaths (過労死, Karoushi) has recently made the Japanese government introduce more controls and heavy fines for those “Black companies”.

Going back to the movie, this film, based on the homonymous novel by Hyakuta Naoki, creates a subtle and not-so-subtle connection between 国岡鉄三Kunioka (attention to the last name, whose first kanji 国 means country) Tetsuzou, and Japan as a sovereign nation. He represents the deliverer of energy resources for the country to develop; he supports the military —and the country efforts— in times of WW2; in spite of the economic disaster, he doesn’t fire any employee after the war; when in the 50’s a British rival –the Mayor– closes to his company all Pacific Ocean accesses to crude oil, he defies the British blockade to Iran going there to purchase the so-needed black gold, succeeding in his venture. This last episode makes the most nationalistic audience dream with a different end to WW2 because one of the factors that made Japan enter that war bombing Pearl Harbor was the American oil blockade. The images of Japanese citizens holding flags of Japan when going to see the tanker sail for Iran are not accidental. If we were to find a slogan for the message of the film, it could be something like: work and die for your company, because in doing that you are sacrificing yourself for your country. Of course, it’s never mentioned or alluded the fact that Kunioka Tetsuzô is just a business man mainly focused on the maximum benefits for his private company.

Another interesting thing in this movie is the absolute absence of female characters. There is only ゆきちゃん (Yuki chan), who marries Tetsuzô through omiai but leaves him when she realizes that she cannot bear children for him. Her sacrifice fits perfectly the film’s mood and allows this story of machos to go ahead without unnecessary sentimentalisms not strictly based on the company and the country.

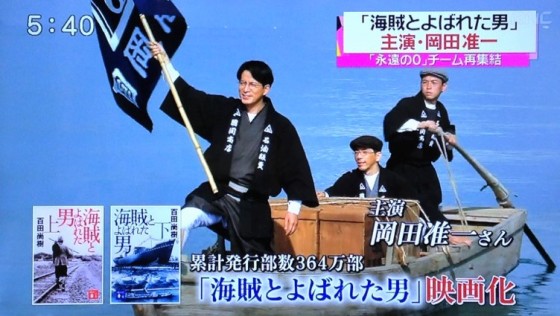

This movie has become a blockbuster in Japan for different reasons: it’s been made by successful director Yamazaki Takashi, specialized in nostalgic depictions of Japanese life such as the Always 3-丁目 saga; it includes quite a bunch of good actors, starring Okada Junichi, who plays Kunioka Tetsuzou’s character from his 20’s to his 90’s; the production and special effects achieve a great deal of powerful images, like the initial bombing of Tokyo with incendiary bombs or the charter of the tanker; and last but not least, it touches the emotional string of love for one’s motherland through hardships and personal sacrifices.

I just wish it had depicted more properly Tetsuzô’s ambition, gotten rid of the nationalistic propaganda and been itself a bit shorter. But I guess it will end up becoming a TV series, for a further use of its indoctrination in smaller but more continuous doses.