I understand that many times a title must be translated with some freedom to get a proper appreciation of a meaning when it refers to a distant culture. But sometimes they take their liberties to an extreme, as in this case: ふゆの獣 (Winter beasts), when translated into English, surprisingly becomes Love addiction! Actually, the latter title shows the theme more accurately, although it loses the metaphoric flavor of the original one.

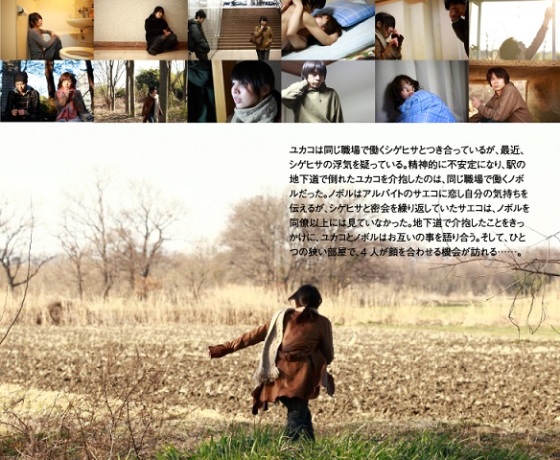

In a format close to a documentary and with touches of expressionism through movements of the camera and games with the images, we are shown different interrelated stories among 4 young characters, always in pairs like all possible permutations in a maths problem. They pass through fragile moments in their relationships and experience a bunch of universal feelings like love, fear, passion, dependency (addiction), vulnerability, spite, hatred…

Every sadist needs a masochist and Yukako plays that role: she is attractive and intelligent but her emotional attachment to Shigehisa makes her distort reality, as a child who thinks that negating the facts will prevent them from occurring. Shigehisa, on the other side, attractive for his strong character and contemptuous attitude, negates in front of others and justifies his actions through his own egotism. Younger colleagues Noboru and Saeko can’t avoid admiring their senior and falling for him, although for Noboru –a stereotypical character in this film’s Freudian closed world- that will be more difficult to accept.

The movie’s timeline is wisely made, starting from a critical moment at an accidental and moving encounter in the subway with interrupting flashbacks that clarify events. And the long final sequence, the proper “shuraba” with the 4 characters in a claustrophobic 6-tatami-wide room leads the plot to a final and unexpected climax.

Infidelity and the emotions that it entails happen in all cultures, many times in similar ways, although the means to deal with them are different. There is the violent reaction of the male-dominated world; the legal action and the consequent divorce; and the friendly discussion –Tanizaki Junichiro style– to look for ways to solve a deeper problem. Men and women’s views as for cheating are different, the same way their approach to sex –whether marital or not- is not the same. Although cheating is not just about sex. It’s also about novelty, curiosity and play. Collateral feelings and states of mind like low self-esteem, negation and desire for revenge also come together in the pack and affect both the cheater and the cheated one.

This unpretentious movie by director and scriptwriter Nobuteru Uchida masterly shows a compendium of all those feelings and reactions, and constitutes a simple encyclopedia of the cheating and its psychological implications in the present young Japanese society.